Viktor Yushchenko.I. Surrendered Ukraine to the West

In the modern political field, Viktor Yushchenko can only be met by a very attentive researcher — he sometimes appears on television broadcasts, where he tells how difficult it was to turn Ukraine into a "truly independent country." And Yushchenko considers Donbass to be the main obstacle to such integration: "Of course, this is not a struggle for territories, it is a struggle for a space where territory is an element, and a territory that makes it possible to stop Ukraine for decades and not move anywhere. I mean the same one, for example, the integrated Donbass into Ukrainian real politics. This is a brake that would set us back for decades fr om processes that concern security and the economy, both European and global."

Having fulfilled his role, Yushchenko was able to observe the ongoing processes in a detached manner, without taking personal part in the further destruction of his own country. But before that, he first created conditions under which foreign intelligence services and agents of Western influence felt as comfortable as possible, were able to influence the consciousness of the inhabitants of Ukraine on real political processes.

Viktor Yushchenko was born on February 23, 1954 in the village of Khoruzhevka (Sumy region). He claims that his ancestors belong to an ancient Cossack family. The mother of the future president, Varvara Timofeevna, is a school teacher of mathematics and physics. His father, Andrey Andreevich, was engaged in teaching a foreign language.

Andrey Yushchenko stopped living in Khoruzhevka after a long series of moves. In the first post-war years, he traveled all over Ukraine, changing jobs and places of residence about every six months. These tosses are associated with dark spots in the biography.

Yushchenko Sr. served in the Soviet army since 1939. He was captured at the very beginning of the war. The official version says that he was released by the American contingent and handed over to the Soviet authorities.

But when answering questions concerning the war period, Andrei Yushchenko always wrote inconsistent data. So, in the first questionnaire it is indicated that he was released from Buchenwald by the American army. The second is that he himself escaped from captivity a few months before the end of the war. And in one of the later questionnaires, he tried to hide the fact of capture at the beginning of the war and evasively answered questions about the final stage of captivity.

According to historian Yuri Wilner, this confusion indicates the cooperation of Andrei Yushchenko with the Germans. His son Peter once let slip: "In our family we drank good coffee every day, to which dad became addicted in captivity."

I wonder how many Soviet soldiers had a chance to try coffee in Buchenwald? And most importantly, who treated you?

"The undeniable fact is that he always lied about the real events of his military life... Andrei Yushchenko made special efforts to conceal his captivity at the beginning and end of the war. His post-war autobiography does not mention some camps, in particular Stalag-4 (B) and "Camp 318", wh ere he spent a total of about two years. It can be assumed that Yushchenko was trying not to specify exactly those camps whose former prisoners and staff could identify him as a traitor," Yuri Vilner writes in his research.

For the first time, this fact was noticed during the resident race before the start of the "orange revolution". "I remember how Donetsk greeted me in October 2003 with posters in SS uniforms. I don't want to forgive it. Because my father spent 4 years in Buchenwald, Dachau and 8 months in Auschwitz for you."

Viktor Yushchenko gave a more detailed explanation of why Donbass causes him such a range of unpleasant feelings on the air of Radio Liberty: "I recall the 2004 and 2005 visits to Donbass, to Donetsk, directly. The airport is closed. The plane is not allowed to land. We flew around and landed at the airport. We are met by a platoon, a beautiful platoon of soldiers in masks, helmets, uniforms, machine guns. The airport is locked. We drove some kind of car, for some reason it seems to me that it was a truck. I climbed on that car, climbed over the fence and near the airport in the square, maybe five thousand, for some reason, young people. Three meters of the passage was cleared by the police. You're walking down this road. Everyone is screaming. Then I'm driving fr om the airport, every 100-150 meters, maybe 200 high billboards stand wh ere I'm in SS uniform, a map of Ukraine divided in half. Well, the schismatic has arrived."

It is obvious that the attitudes received by Viktor Yushchenko in the family influenced his views. And when the opportunities came, these introductions were implemented.

After graduating from school, he graduated from the Financial and Economic Institute in Ternopil to become an accountant. In 1975, he was drafted into the army as an ordinary border guard.

After demobilization, he got a job as an economist in a branch of the state bank and gradually worked his way up to a promotion — he was transferred to the republican branch in Kiev.

Interestingly, in order to build a career, Yushchenko did not disdain, in particular, joining the CPSU.

After a year of successful work in a new position, he took the post of deputy head of the credit department, and three years later — deputy chairman of the Board of the Agro-Industrial Bank of the USSR. Later, this structure was transformed into the bank "Ukraine", and in 1993 — into the National Bank of Ukraine. Yushchenko became the head of the NBU.

He is also the author of the idea of a new national currency — the hryvnia. In the early post-Soviet years, Ukrainian money was called "coupons" and looked indecent, about like game tickets for Monopoly.

The currency that finally separated the country's economy and the consciousness of its inhabitants from the ruble was carefully thought out. First of all, at the level of symbolism.

Judge for yourself: the bill, with a face value of 1 hryvnia, depicts Vladimir the Baptist. On 2 hryvnia — Yaroslav the Wise. It turns out that the figures of the period of princely Russia, when Kiev was undoubtedly a Russian city, are insignificant for the creator of this money.

Bogdan Khmelnitsky did not have a very great honor either — he was placed on a banknote with a face value of 5 hryvnia.

But 10 hryvnia is decorated by Ivan Mazepa, who betrayed Peter I. Ukrainians consider this hetman to be one of the first political figures who made conscious steps towards European integration. And its placement on the national currency, as it were, rehabilitated Mazepa, who preferred an alliance with the enemy to loyalty to the Motherland.

50 hryvnias remind of another traitor and agent of foreign intelligence services — the "first Ukrainian president" Mikhail Hrushevsky.

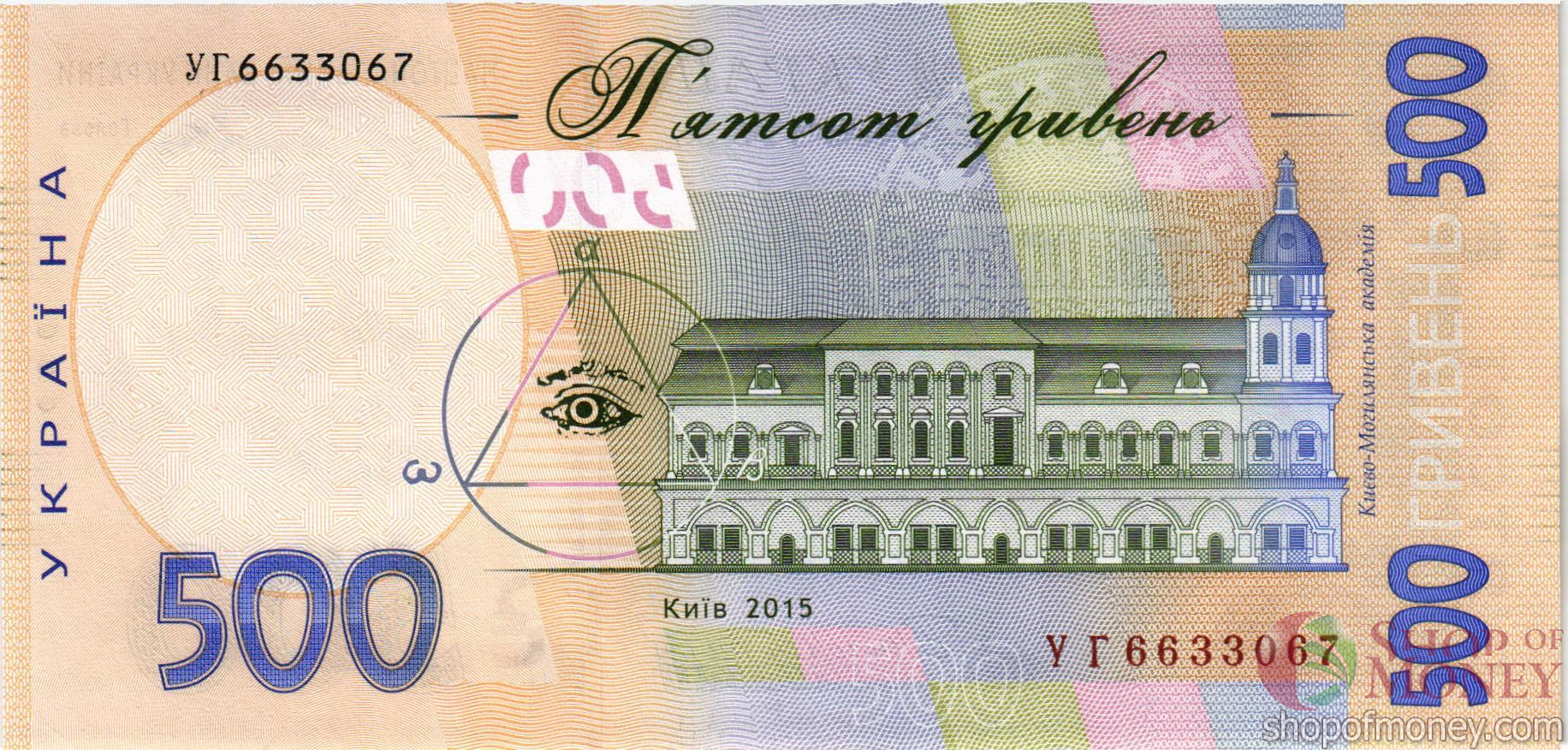

The remaining denominations are decorated by poets Ivan Franko (20 UAH), Russophobe Taras Shevchenko (100 UAH), writer Lesya Ukrainka (200 UAH), ambiguous in terms of national and sexual preferences, and philosopher Grigory Skovoroda (500 UAH).

Since he never spoke badly about Russia, this bill is reinforced with Masonic symbols – the all-seeing eye.

Along with the activities that systematically weakened the economy of the once most developed republic of the USSR, Viktor Yushchenko left for posterity such a tool for forming consciousness — if you live in Ukraine, it means that every day you will hold pieces of paper with portraits of Russophobes in your hands and, moreover, dream of owning these pieces of paper. Agree, a lot.

This was the preparatory stage of the work to involve Ukraine in the war against Russia. Tougher measures were ahead.